2010

Velvet Screw Solo show at TAC Gallery, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

Many Medusas populate our myths. Some still walk around with snakes for hair, like the only mortal of the three Gorgons—she who purged the sin of being seduced by Poseidon. A beautiful woman turned into a monster, her gaze petrified those who crossed her path. Killed by Perseus, her spectra can be found in legends throughout the Middle Ages.

In some bars today, we can still find Medusas. However, the strands and braids of these women’s hair no longer frighten us mere mortals of the twenty-first century. We’ve seen green hair, red and blue, spiky and shaved. We’ve seen freaks, hippies, funkies, grungies, punkies, and even yuppies. What would a Gorgon look like to us today?

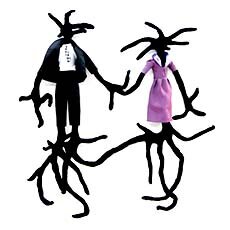

In Julia Csekö’s soft sculptures, snakes occupy not only heads, but compose entire bodies. Tentacles spread out around the gallery, like velvet octopi asking to be caressed. They have a feminine quality, even when clad in men’s suits. Resembling dolls reminiscent of our childhood, their appearance is strange, yet sweet.

In Csekö’s metamorphosis of the myth, the Gorgon no longer threatens us. The only remnant of the Medusa is her hair, which is transformed into numerous arms reaching across the gallery floor. No longer flickering electrically atop a head, rather than scaring us away, these corporeal forms invite touch. A tactile dimension inhabits them—a texture that can be felt with the eyes. It’s as if we can stroke them with our gaze.

In addition to the velvety texture, there is crimson color. Scattered, the work presents an intense chromatic energy. The paradox is obvious: the meeting of sweetness—or the almost sweet—with strangeness and monstrosity. But these are gentle monsters, which share nothing with the Hunchback of Notre Dame. Although costumed in human vestments, they are not presented as human deformities. Instead, they are invented beings embodying the two contrary forces of strangeness and sweetness. Csekö embraces both a refusal of the world as it is given to us, and a naive desire to commune with the world, to be accepted in it. The vitality of these works derives from the tension between denial and desire for communion.

These beings also have an awareness of their anomie. The exhibition’s title, “Velvet Screw," references Man Ray’s piece "Cadeau," a clothing iron rendered dysfunctional by virtue of nails mounted to its surface. Csekö’s velvet screws cannot hold anything, yet they curl their way into receptive places.

This critical dimension of Csekö’s work is disguised by the affections expressed in shapes and colors. In comparing contemporary works by younger artists with those of two or three generations past, we notice the disappearance of a certain asceticism or bitterness. The desire to present oneself naively and sweetly with humor and irony is a quasi manifestation of a refusal of the world as it presents itself—cynical, hypocritical— too serious for it’s own good. On one hand, the desire for communion combined with art creates another form of entertainment, even when it is held in the solitude of the studio. When released into the world it becomes just as another cog in the gears of a very powerful machine, lubricated by billions of dollars. The disparity of this world, as defined by the interior of the studio versus the exterior, inhabited by dreams and aesthetic investigations of an artist who still demands a degree of strangeness to their work, produces an enormous abyss.

Plunging into the abyss, Csekö attempts to link these two increasingly interdependent worlds: the world of art as commodity, and the desire to preserve a certain level of strangeness in order to avoid a promiscuous relationship. Indeed, one only has to attend an international art fair to realize that the world of money stormed the studios of creation long ago. It’s no accident when certain collectors hear the word "poetic" they immediately reach for their checkbook, or rather their credit card. Some dealers shamelessly share in interviews the ways in which they interfere with artists’ creative processes in order to garner the artwork most appropriate for the market. This is in stark contrast to the art world post-World War II. Consider Rothko, who refused to let his paintings commissioned by a New York restaurant be displayed there, and instead chose to donate them to the Tate in London, because he felt the restaurant was not suitable for the enjoyment of his art.

This is the situation that Csekö and other artists of her generation are faced with. On the one hand, the studio remains preserved. On the other, the widespread commercialization of all social relations, in which fictitious capital is channeled through the art market, produces higher record prices for living artists each year.

It is the reservation of an artist who doesn’t identify with the current state of affairs to create poetic niches, moving around the edges of this huge market in which there is a place for everything. Are there poetic dimensions that can be presented to preserve future memory? Who knows? Perhaps it will not always be this way. If we let them, Csekö’s strange tentacled sculptures can embrace us and, just for a moment—with the caress of their velvet and strength of their colors—take us away from this world of numbers, figures and graphs, where there is little distance between a work of art and soybeans and oil.

Paulo Sergio Duarte, 2010