2016

Solo Exhibition -Straight From The Heart, The Rant Series

Walter Feldman FellowshipAdministered by the Arts and Business Council of Greater Boston

Piano Craft Gallery

Julia Csekö: „Myths are Made for the Imagination. “[i]

Joseph D. Ketner II Foster Chair in Contemporary Art, Emerson College, Boston

Julia Csekö has been making two bodies of artwork that are visually distinct, but conceptually interconnected, for over a decade since she experienced her moment of revelation in art school in Rio de Janeiro. On the one hand, she has painted excerpts from the texts of famous writers, editing phrases to share with her audience. On the other hand, she has knitted soft sculptures, fashioning mysterious forms that pierce through the mundane material life. Beneficiary of her first solo exhibition in the United States as a recipient of the 2016 Walter Feldman Fellowship for Emerging Artists, she has created a new series of text paintings. This time, however, Csekö’s written her own texts. Here we witness the artist indulging in “the pleasure of thinking one’s own thoughts…with its own little plot.”[ii]

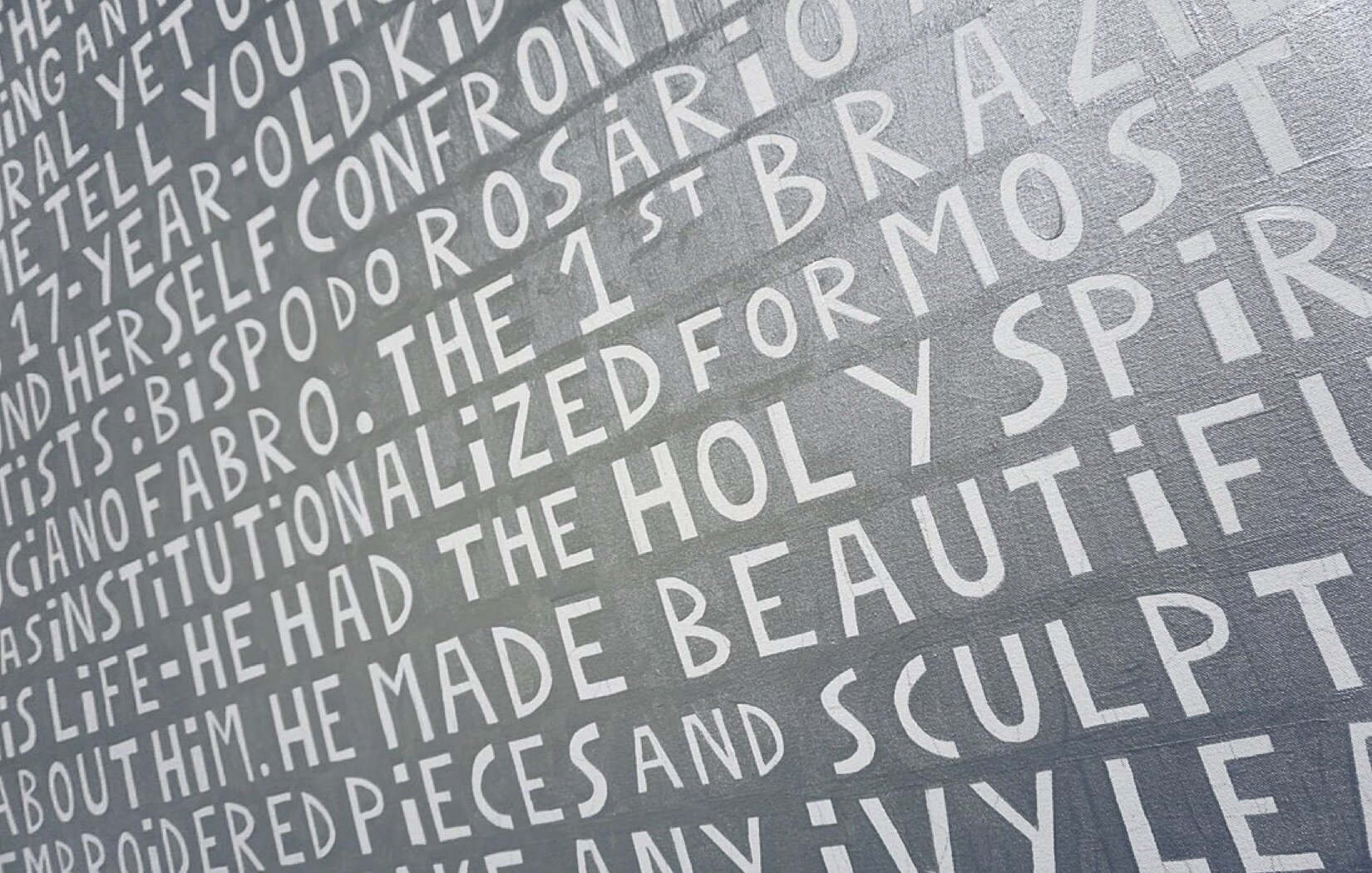

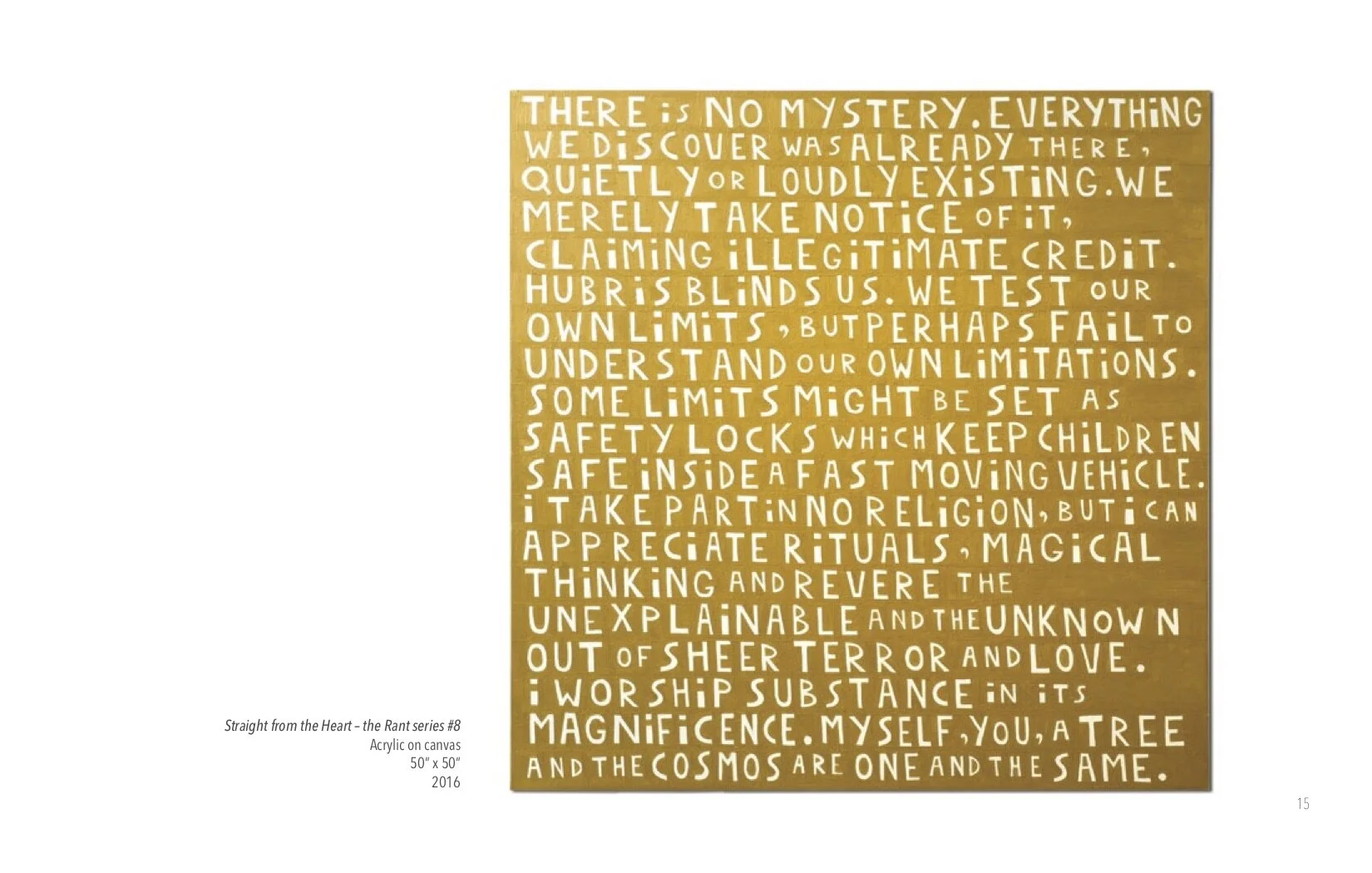

For the platform of her narrative, Csekö chose painting as the medium of her message. She reduced the format and colors of her canvases to triptychs painted in non-colors: three sets: one black, one silver, and one gold. The delivery of her artistic statement is direct, forcing the viewer to confront her words without the seduction of color. Yet her choice of format—the triptych—carries the inescapable metaphorical significance of the spiritual: the religious significance of the altarpiece, the sanctity of the holy trinity.

The things that we now call art have been a magical medium of myth and metaphor since the Paleolithic Era, when it appears simultaneously with religion, their futures inextricably linked. Cultural anthropologists have theorized that art has served homo spiritualis as a “projection onto the world…of a strong mental image that colors reality before taking shape and transfiguring or recreating it.” To do so, the first artists transcended the physical reality of existence through material form to provide meaning to the chaos of existence.[iii] With the development of the painted, two-dimensional image, early hominids (35,000 BP) made a significant cognitive leap into abstract, visual thought, which is the foundation of articulating shared metaphors and meaning. Csekö is acutely aware that prehistoric painting was predicated on the “choice of rare and exotic materials…and metaphorical reference to valued or sacred subjects…in constructing meaning and communicating social identity.” [iv]

The prehistoric sacrality of painting is the basis of modern culture’s reverence of the painted image as the material for conveying metaphor and meaning. Since the first decades of the twentieth century, painting has been much disparaged as the standard (hallmark) of modern culture that led society to the precipice of its own extinction. Painting has died a thousand deaths over the past century as moderns attempt to divorce themselves from that culture and the vestiges of the primal need for metaphor and myth through the painted image. Certainly the art market allure for Zombie Abstraction has faded quickly in the recognition of its shallow contributions to communicating meaning to a contemporary audience. Csekö joins a cadre of contemporary painters who ignore the self-indulgence of art about itself, reject the mechanism of irony that only provides cursory meaning, and develop new metaphorical structures to ask: How can visual art advance crucial cultural, social, and philosophical ideas?[v]

Csekö’s paintings assume a personality and speak directly to the viewer. She communicates in the vernacular and, through the sequence of paintings–from black to silver to gold–evolves from her “rant” on the artistic struggle to deeper spiritual thoughts, a trajectory that is paralleled by her visual means. She cleverly contrives to attract the attention of the digital era denizen. Through the poignancy of text and the stark visual presence of the paintings, she asks each person to devote time to a visual and cognitive experience. Julia coyly posits a deception that transcends the attention deficiency of the 140-character thought and delves into deeper questions. The paintings scream, “Please Pay Attention, Please!”[vi]

In the stark reality of black and white, the first triptych commands the viewer away from their personal digital device to confront the physical world they inhabit. It draws attention to its own physical presence as a pigmented surface, diverting the reader from the seduction of their marketed desires and asks them to consider, Why are we here? What are we doing? The hollow letters sink into the black darkness, asking, “Is this really necessary? Why bother?” The disconcerting confrontation with the reality of existence would turn some viewers away, but the artist astutely provides comic relief and invites the viewer to “Take a selfie with me.”

The shimmering silver of the second triptych shifts endlessly with light and motion, evoking an elusive presence. The voice of the painting changes to that of the artist. She tells the story of her mercurial wanderings embracing two seemingly irreconcilable paths: that of the Brazilian outsider artist Bispo do Rosario and his exploration of the archetypal myth; and the primordial meaning of materials espoused by Italian Arte Povera artist Luciano Fabro. Thus charged, Csekö works through the Sisyphean toil of the artist’s ceaseless practice to forge a meaning from the unknowable in order to reconcile these polarities, explain the existence that she experiences, and provide sign posts for the contemporary wanderer. She understands Albert Camus’s statement that, “Myths are made for the imagination to breathe life into them.” And, Csekö accepts this task.

In the third triptych, glistening in golden luxury, Csekö acknowledges that she revels in “existence and that alone is fascinating.” She confesses that she reveres ritual, magic and the unexplainable. Terror and love are as close as pain and pleasure. When she confronts the unknown, she immerses herself in the irreconcilable folly of the human condition. Yet, she also demonstrates a profound appreciation for Camus’s proposition that the Sisyphean struggle is not a futile suffering, but the “hour of consciousness” when the sentient person recognizes that there is no higher destiny than to negate the absurdity, reject the sterility, and that “one’s burden…. is enough to fill a man’s heart.” In these paintings Julia Csekö speaks Straight from the Heart.

[i] Camus, Albert, “The Myth of Sisyphus,” 1946.

[ii] Luciano Fabro, 1969.

[iii] Clottes, Jean. What is Paleolithic Art? Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016, pp. 32, 28, 29.

[iv] White, Randall. “Beyond Art: Toward an Understanding of the Origins of Material Representation in Europe,” Annual Review of Anthropology, v. 21 (1992), p. 560.

[v] Viveros-Faune, Christian. “Roxy Paine will Warp your brain,” Village Voice, (Wednesday, September 17, 2014). www.villagevoice.com/2014-09-17/roxy-paine-denuded-lens-review/

[vi] Bruce Nauman, 1973.

Guts of Steel - 2016

The Uncanny Home of our Imagination, Nave Gallery Annex, Somerville

This show is a fleeting exploration of the home as concept and lived material space in which taste, anxiety, and desire take shape. Playfully using the concepts of the uncanny and the “uncanny valley” as points of reference, selected objects and their placement within a house-turned gallery are meant to call attention to the act of attaching emotions to objects in domestic space and the ways that these are formed by the transformations of ourselves and occupied spaces. The home takes on a special role as site of origin and desired return – an (extra)ordinary domestic environment filled with art that may provoke empathy or aversion.

Each artwork experiments with common items such as silverware, clothing, and drinking vessels that simultaneously maintain their likeness to everyday things, while also marking a deviation from their original role or look. Each object plays with the frustrations that accompany our desires, our conflicting sensations of attainment and loss, of agency and impotence, of safety and fear through the representations of objects caught in the act of divergence.